Playing jazz bass

A brief crash course.

I enjoy writing short tutorials to get people started on something that may have seemed intimidating to them before, and I thought it might be fun to write up something that isn’t related to software but that I have thought a lot about in the last 15 years: jazz bass playing.

A few basic patterns that you can repeat over nearly any chord will get you pretty far. Any rock or classical bass player should be able to pick these up quickly. It should also work for any guitar player, because both electric and upright basses are tuned like the low four strings of a guitar. (Of course, the upright lacks frets, so you have to put your left hand’s fingers where the frets would be.) This crash course can be useful to keyboard players as well, who can treat it as a guide to what to play with their left hand for jazz tunes.

You can think of just about all jazz as being composed of 7th chords: major 7th, minor 7th, dominant 7th, and, less often, diminished seventh, or half diminished chords. These each consist of four notes, and the distances between the notes are what make them sound different–for example, the first two notes of a major 7th are a major third apart, and in a minor 7th they’re a minor third apart. Jazz musicians who see a three note triad chord like D minor may just add the seventh anyway, treating it as a D minor 7th. For a dominant 7th such as G7 in the key of C, jazz musicians since the advent of bebop in the 1940s sometimes add more notes to the chord such as the 9th, 11th, and 13th notes of the root note’s scale. They may even shift some of those added notes up or down a half step so that you see a fancy chord name like G#9. As a bass player, just think of that as a G7. To summarize, it’s simplest to think of it all as 7th chords.

There are some classic patterns that bass players typically play over these 7th chords, and if you learn a few of them and the notes of the chords, you can play simple jazz bass lines. Guitar players know that if they play the notes of an A minor 7th chord and then move their left hand one fret up the neck and do the same thing, they’ll be playing a Bb minor 7th, so learning how to play all the chords means learning only a few patterns that you can play up and down the neck. The same applies to these jazz bassline patterns.

A walking jazz bass line is nearly all quarter notes, so when you see “1357” below, for a given chord in a given bar played in 4/4 time, you would play these four notes as quarter notes: the root of the chord (the 1), the 3rd, the 5th, and the 7th. For example, over an A minor 7th chord, 1357 would mean playing A C E G.

For each of these patterns, we’ll look at how you would play them on the first four bars of the jazz standard Autumn Leaves. (Compare Nat King Cole’s version with Miles Davis’s; Miles’ fifty-second intro puts off the actual song a bit.)

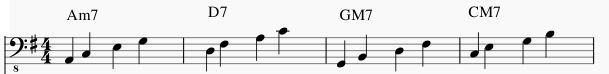

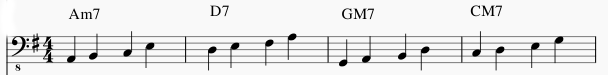

1357

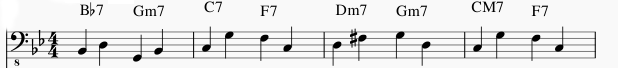

This is probably the most important pattern, but not the one you’ll use the most. It’s just an arpeggio of the chord–that is, the playing of each note of the 7th chord from the root up. It’s an important pattern to practice with any given song because it helps you to really understand the song’s structure. Over the first four bars of Autumn Leaves, this pattern would look like this on a bass staff (click the play button underneath it to hear the bass line with a piano and drums generated by the excellent open source scoring program MuseScore):

Repeating the same pattern for four bars is not something you’d want to do when playing with other people, but for this pattern it’s something worth doing for an entire song while practicing on your own because it helps you to get to know the song’s chords better.

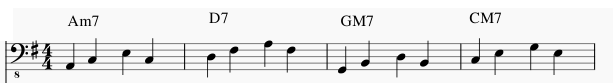

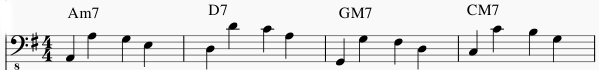

1353

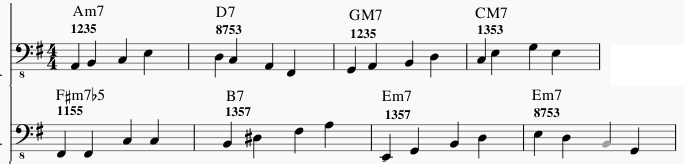

This one is so useful that I use it too often when I’m on automatic pilot. You can’t go wrong with it. I mentioned above that the main difference between a major seventh chord and a minor seventh chord is the “3” note; this pattern really brings that out while still hitting the most important notes of the chord from a bass player’s perspective–the root and the fifth–on the crucial first and third beats of the bar. Here it is over the start of Autumn Leaves:

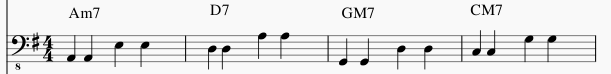

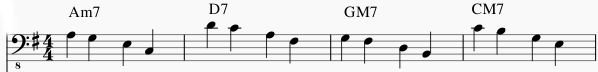

1155

This seems almost too simple, but it sounds great if you give it a strong swing feel on a song like Duke Ellington’s Satin Doll. Here it is over Autumn Leaves:

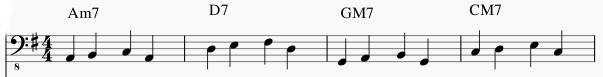

1231

The 2nd note of the chord’s scale is not a chord tone, but here it leads to a chord tone on the crucial third beat. This is the first pattern we’ve seen that doesn’t always have either a 1 or a 5 on the first and third beat; the 3 on the third beat brings out the color of the chord more. In Autumn Leaves:

1235

Similar to the last one, and similarly useful. In Autumn Leaves:

1875

The 8 here really refers to the 1, but an octave higher. This is our first pattern with a 7th in it. In Autumn Leaves:

If you replace each quarter note in that with two swung eighth notes, you’d have a classic Chicago blues bass line, although major seventh chords don’t come up in Chicago blues very often:

(John Paul Jones’ bass line in Led Zeppelin’s How Many More Times is a variation on this: 1 8757 1 8 7 5.)

8753

Going down from the root of the chord through the chord’s other notes is also great. Again, you have the 1 (an octave higher this time) and the 5 on the first and third beat. In Autumn Leaves:

Half bars

Jazz songs typically have one chord per bar. There are songs ranging from I Got Rhythm (and the hundreds of songs based on it) to John Coltrane’s Giant Steps that are mostly two chords per bar, but in most jazz you’ll see one chord per bar with the occasional two-chord bar at the end of a four- or eight-bar phrase. If you play the chord notes 13, 15, or 85 over each half bar, you’ll be fine. Here are the first four bars of “I Got Rhythm” using 13 13 15 85 13 85 15 85:

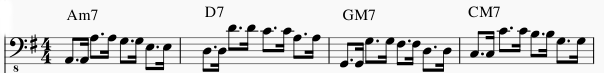

Putting some together

Good bass playing mixes and matches these (and more) patterns. Below I’ve written out a bass line for the first eight bars of Autumn Leaves, labeling which of the patterns above is used in each bar:

Note how all the patterns listed above start with the root note of the chord. This is a solid, dependable thing to do, and greatly aids the jazz bass player’s job of showing the others what chord is being played. A step toward more advanced bass playing is getting away from this–for example, starting on the 3 or the 5 of the chord–while still making it clear to the rest of the group exactly which chord is happening. (They should already know, but still, you and the drummer and the piano or guitar player are providing the cake of which the other player’s solos are the frosting.)

Using more non-chord tones, the way 1232 and 1235 do above, is also a way to move past beginner status, as is moving beyond playing four quarter notes for every bar. As a first step to moving beyond the patterns above, try substituting 8 for 1 in more of the patterns, and try coming up with your own combinations of 1, 3, 5, 7, and 8. And, listen to great bass players. My favorites are Paul Chambers and Ray Brown, but if you listen to older, pre-bebop jazz, you’ll hear more of these simple patterns come up more often.

Share this post